A few years ago I, in common no doubt with all other members of The Private Libraries Association, was asked by the Chairman to write a little piece about 'how they came to books and what are their feelings towards them'. I wrote a piece and sent it off. Some years later (the editorial tasks must have been horrendous!) the book, entitled a modest collection, was published. It is a handsome book and full of interesting stuff but I strongly suspect that each recipient of such a book checks with pride their own appearance in print and then puts the tome carefully on the shelf. I have certainly had no indication whatever that anyone at all has read my piece! It may well not find anyone interested here either but I put it up anyway, hoping that one or two may be amused.I cannot remember a time before I loved books. As a child I hoped to be given books for Christmas and I would visit bookshops, especially second-hand ones, with excitement from an early age. I am ashamed to remember that, as a teenager at boarding school, I worked out a foolproof method of pilfering from my favourite warren of a bookshop. It involved visiting the shop dressed for tennis and carrying a racquet and box of balls. The clever thing was that there were no balls in the box. I think that I was much too scared a lad to have carried out the scam but I did emerge from that shop with many legally acquired treasures such as five leather-bound volumes of Pope’s Iliad which cost 15/- and how I can remember the smell and the thrill as I opened one of those romantic objects . . . books which had been made and actually handled by people living in the eighteenth century.

‘I cannot remember a time before I read books’. Had I started this piece thus, rather than as above, few might have noticed any difference but the fact is that the latter is as untrue as the former is true. I was, and remain, a very slow and unhappy reader. I simply cannot concentrate on the words. If I am trying to read for pleasure I soon nod off, even if I am not reading in bed. If I am reading because I have to, or need to, I find myself thinking about something else after a couple of sentences . . . just as I did in prep while trying to read the designated chapters about the Thirty Years War. It is the equivalent of the small boy in class who keeps looking out of the window and, indeed, I was that very child. So, if I did not devour pages of text, for study or stories, like the usual sort of bookworm, why did I like books so much?

The simple answer to this conundrum is . . . pictures. The best books of my childhood had gobbets of text on each page but these were surrounded by images in which I could be lost, worlds in which I could wander and in which I could be more alive than in the atmosphere of fear at school and of boredom at home. Actual illustrations (magical line drawings by Heath Robinson, John Minton and Mervyn Peake or summery lithographs from Curwen and other presses transferring drawings of Babar and Orlando to metal plates from grained plastic sheets, for example) were marvellous in themselves but my favourite books were those which used the double-spread like the stage of a theatre or the wide-angle viewfinder of a movie camera. Swirling vistas of imagery cover the page and the paragraphs of text sit safely surrounded by the scenes they describe. In some artists’ work it is the all-over tapestry of the treatment that is satisfying while in others (and these appealed more and more) the effects were achieved by artist and book designer with less rather than more. I would let my eyes wander round an expanse of land, sea and sky and suddenly realize that it consisted largely of white paper and the magic of an artist.

Pope’s Iliad wouldn’t have had many pictures in it, I hear you comment. No, but it did have glorious initial capitals and stretches of large italic type and ligatures and long Ss and all sorts of exciting ways of placing stuff on a page which, as a schoolboy, I found intriguing but did not understand (like sex) and certainly did not know that it was called typography.

For a time after becoming an educational publisher, I attempted to collect old schoolbooks but soon found that most of the Victorian period ones, which were available on the shelves, either had no pictures in them or were unimaginatively laid out with ‘improving’ engravings. Sadly, lovely ones from earlier times, which I had seen photographed in books, were fiendishly rare and expensive. Carefully locked away in glass-fronted bookcases, posh ‘limited editions’ are all preserved while books made for children are now rare, having been loved, scribbled or torn to pieces by the little monsters.

I soon began to concentrate on Illustrated Books Of the First Half of the Twentieth Century. There were the Pre-Raphaelite wood engravings, Beardsley, Laurence Housman and early Heath Robinson at one end and, crucially, at the other end, the wonderfully inventive post-war publications (so often from Houses run by European refugees) on war-economy paper with no margins and, if you were lucky, a dust-wrapper with another on the back, liberated from the over-long print run of some other title. The very best of these, for me, were those illustrated by the neo-romantic painters with whom I had been fascinated since exploring the various Cork Street galleries as a teenager. At that time I could not afford the paintings (lost time has been made up for to a certain extent now, I am happy to say!) but often the images by Keith Vaughan, John Piper, Graham Sutherland, Edward Bawden et al in these volumes took the form of autographic lithographs and, thus, represented (and still do, of course) a wonderfully inexpensive way of acquiring original prints by my favourite artists.

In those early days, mine was an unfashionable area for collecting. In special cabinets, booksellers would prize Rackham and Dulac books but these, to me, were simply books of text pages with reproductions of paintings glued in. My quarry, with the help of my ‘shopping lists’, John Lewis’s The Twentieth Century Book and Rigby Graham’s PLA booklet, Romantic Book Illustration in England, 1943-1955, could be found anywhere and picked off the ‘ordinary’ shelves. I would spend an hour in a new shop and come out with a cardboard box full. This honeymoon period was not to last, of course, and I am happy that I did not let up while the going was so good.

I did lash out on some major treasures when funds allowed. When we moved out of London to our paradise in Wales, I was moved when the unrepeatable Alan Hancox sent a postcard to wish us well, saying that he was pleased that his copy of the Gill Four Gospels had ended up so close to Tintern Abbey!

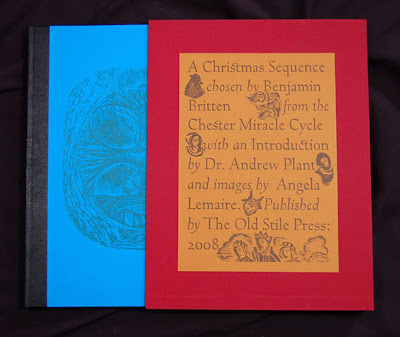

Active collecting ended when we started to produce books of our own. The Old Stile Press had started when I was still a full-time publisher and developed over a number of half and half years before becoming all-consuming when I was able finally to bid farewell to London. Our pattern (almost from the beginning) of working with artist/printmakers on books in which image was as important as words and the design of the book as a completely integrated whole was foremost, has developed over the years. We are going strong, with an eager following among librarians and collectors across the world and, as I write, I have exciting projects being worked on by artists which will keep me busy hand-feeding sheet by sheet well into my dotage.

It is a happy and satisfying thought that, had that fifteen year old snuck into that bookshop, all those years ago, and found one of the books we are now producing, he might just have liked it enough to slip it into his empty tennis ball box!